As I passed the reasonably priced bags of horse manure at the end of the driveway and turned my muddied sneakers towards the gate beneath the swaying gums, I was met by a man who has proven himself more than adept whilst holding both a Sherrin and paintbrush.

Although Jamie Cooper's once sandy hair has begun to take on a more silver tone these days, his physique, and firm handshake, belonged to someone that could still get a kick today.

Having exchanged pleasantries beyond the gate of his Hurstbridge property, the soon to be 57-year-old ushered me towards his studio - where he has built his legacy as the iconic Team of the Century artist.

After passing through the beaded curtain that would prove useful at shooing flies when the surrounding paddocks were golden rather than green, my eyes both widened, and lifted, to survey the painted guardians of Cooper's workspace.

At one end of the converted barn, stood a barefooted and behemoth likeness of former Cricketer, Jeff Thomson. Staring him down from the other was a multi-metre high portrait of former Fitzroy champion, Kevin ‘Bulldog' Murray.

Despite anticipating a shirtfront from the oil painting of the 1969 Brownlow medalist – a man who would likely tell you that his appearance has never been reminiscent of one - I joined Jamie in the lounge to talk about his life on both sides of the boundary line.

A conventional commencement

Like almost every young Victorian, Jamie Cooper always wanted to play VFL football, and although his post-playing days have been anything but conventional, his pathway to the big league followed an orthodox route.

“It was back in the days of the zones,” Cooper told Zero Hanger.

“I was playing at Surrey Hills in junior footy and that was in the days when scouts would come down and have a look at a few people around about the 16 and 17-year-old mark.”

After making his mark as a schoolboy, the inevitable invitation to join his allotted club arrived in the mailbox.

“From there, I was asked to come down and train with what was the under-19s at Fitzroy, and then made that squad, then went up to the reserves, and then up to the seniors from there,” the former Lion explained.

“That was the pathway then, as I don't think the draft was a big thing then.”

With a studded boot in the door at the Junction Oval, the first chapter of Cooper's life in football had begun. A period that the portrait painter can still paint vividly.

“It was fantastic!” Cooper said, as his lips curled upward.

“For me, it was a dream come true because I had always wanted to play footy when I was a kid. So, getting selected for the under-19s was a big deal for me, and I thought ‘if that's as far as it goes, great'.

“The first year I played [1982], we actually won a Grand Final at the MCG against Melbourne.

“It was back in the days when the under-19s played on the morning of Grand Final day, and then the reserves played, and then the seniors played. So, at the end of our game we probably had about 40,000 or 50,000 people there.

“For a young kid who was in just his first season in, it was amazing.”

With his first piece of silverware obtained as a teenager, the Melburnian continued to climb the rungs set before him.

“From there, getting selected to train and do pre-season with senior list was a big deal, because I was still 17 or 18.”

“Then all of a sudden you are training against Micky Conlan, Bernie Quinlan and Garry Wilson, and all of these guys, it took a bit of getting used to.”

As the apprenticeship progressed, a debut under the watchful eye of pedagogue Robert Walls eventuated in 1984.

SEE ALSO: Five trade targets for Carlton

While Cooper only touched the ball on four occasions, and the Lions went down to the Demons by a slim margin, it proved a day that will remain etched onto his internal canvas forever.

“I still remember it vividly," Cooper recalled.

"It was back in the days when there was a 19th and 20th man and no interchange. It was just when someone comes off, you come on.

“Gary Wilson got injured, and I still remember getting up off the bench and stepping across that white line onto the field.

“It felt like I was entering another world.”

Although Fitzroy were immersed in the club's final period of on-field success, the opportunities at senior level began to dry up for the then graphic design student.

“I was never going to be a champion," the man that was once the boy explained.

"I was always ‘in and out' and off the bench kind of guy, but to be selected in a 20 [man squad] with Conlan and Quinlan, Roos and Pert and Osborne, that was a real thrill for me.

“I had three or four seasons sort of ‘in and out' of the senior team. It was an incredible experience. I learnt a lot, but I don't think footy was what I wanted to devote my every waking moment to.

“I was also doing my art work and I was going to university to study graphic design, so, trying to both of those things, that was pretty difficult.”

Despite never managing more than 13-senior appearances in a single season, should you consult the Encyclopedia of AFL/VFL footballers, you will find that Cooper managed to split the sticks in his last game of 1986.

“If you only kick one goal [for your career], you ‘re going to remember it, aren't you?” the 56-year-old said through a chuckle.

“It was a mongrel floater from about 20 yards out. I dived for a mark and got whacked across the head at Windy Hill and got the free kick about 20 metres out. I remember being pretty nervous and it was a real mongrel.

“It went straight through the middle, but it was a mongrel floater.”

Having kicked a goal as a league footballer, Cooper was able to live out the fantasies of anyone that has ever stood in the outer. However, less than 12-months later, the footballer – then in his early twenties – joined the civilians on the other side of the fence.

From regimentation to agency

Across his time at the Junction Oval and Victoria Park with the Roys, Cooper begun to develop not just his craft as an artist, but the personality to match.

This alternative style – a far cry from the brickies and chippies that comprised the vast majority of the Lions' list – had the man in the number 27 guernsey jovially playing the role of an outsider within the club's four walls.

“I really loved that,” Cooper said.

“There were lots of different sorts of people there, but I was going to art school, so I had a spiky, punk haircut with an ear clip, and I was wearing jeans with holes in them, pointy boots and lime coloured singlets - They would just laugh at me.

“I got on well with them all, as I was a bogan at heart anyway, and I knew how to relate to them, but I was different."

A non-conformist to the core, Jamie said that his identity, both outward and internal, was an authentic display of the joy he was deriving from his dual passions.

“I didn't want to be like everybody else. I was quite happy going to art school and being a bit ‘arty farty', I was having a great time."

"I never felt like they were putting me down, I more felt like ‘you don't know what you are missing out on'.”

With this new wave aesthetic, and a burgeoning skill set, Cooper began to harbour ambitions beyond the boundary line.

“At the end of '87, I had a year in the twos and only played three senior games. I had real kind of plateau year. I also had osteitis pubis, so that was niggling away all year.”

“I was getting restless, and I was ‘umming and ahhing' about what I wanted to do. I was booked in to have an operation and thought ‘bugger this, I think I'll go'.

“I had the end of season review and [David] Parkin had actually heard the whispers about me having an interest in just wandering off. He officially said, ‘we'll give you one more year', but that it would be make or break.”

Despite this ultimatum, Cooper explained that Parkin's experiences as a man, and not just a coach, provided him with an ability to understand the motivations of his playing list.

“He [Parkin] was actually really good because he was actually a teacher, and so was [Robert] Walls, so, they both had an interest in the person as well as the player.”

“They were a pair of the early ones who thought ‘happy person, better footballer', and that the development of the person was important as well.

“Parkin said ‘if you want to make it as a VFL footballer, and there is no guarantee you will, you have to devote your whole life to football because you are not Paul Roos.

“He said ‘do you want to do that for the next 10 years?' and I was like ‘…not really'.”

Now in his fifties, Cooper reminisced about his multi-dimensional mindset that he held as a 23-year-old.

“I didn't want to be 32 and I've not been doing anything else with my life, and he [Parkin] was great. He said, ‘I won't hold you back if you want to go.' He also said, ‘you of all people would benefit from doing that because you've got other interests, and you want to follow your art work'.”

“So, I officially retired, but he wasn't fighting to keep me.” Cooper said through a wry laugh.

“I wanted to go travelling, so, I just put a backpack on and pissed off overseas for about four years.”

With his safety net removed, and getting a kick no longer to only avenue to paying the bills, Cooper headed from the oval's confines into the wider world, all the while grasping his dream of making it in the art world.

Sketches, sculptures and toilet brushes

With his pointed boots haven taken him to, and through, some of the world's greatest galleries, Cooper recalled feelings of excitement and inspiration in his journeys away from home.

But it was a similarly strong sentiment that brought a temporary end to his traipsing.

“I fell in love with a Danish girl and went to live in Denmark,” the artist said.

“When I got there, I had to find full-time work within three months of arriving, otherwise I had to leave.

“I was in a town which was kind of a Uni town, so I had to find a job that didn't involve speaking Danish in a place where all of those dishwasher type jobs were already taken up.

"There was actually waiting lists to get those jobs.”

As a quick thinker that still possessed a professional athlete's physique, the former Lion decided to bare all in an effort to make ends meet.

“I thought ‘what can I do where I don't have to talk and I don't have to do anything', so I went to the art school and became one of the nude models,” he said.

“I'd just finished playing footy, so, I was pretty fit and there was something to model from.

“So, I had three months sitting in a room with Danish people speaking a foreign language, not knowing what they're talking about and in the nude. And then all of these little replicas of me starting appearing around – it was really weird.”

When not sitting atop a stool as a subject before a room of aspiring artists, the similarly minded former footballer continued to hone his own craft.

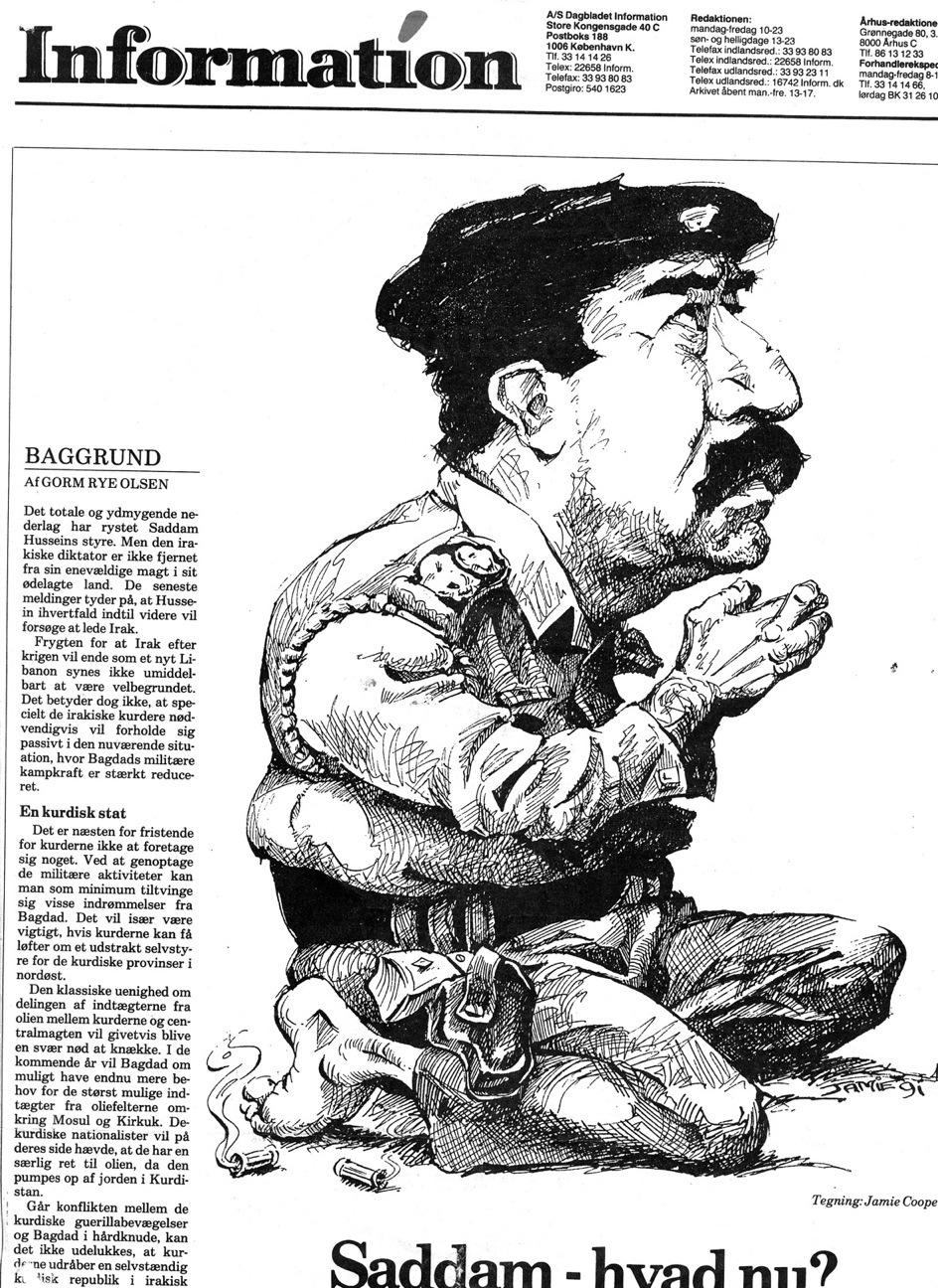

“On the arts side of things, I also sent my work to the national newspapers after I had looked up a bit of [what was going on in] Danish politics. So, I sent some political caricatures into the newspapers in Copenhagen, and one of them picked them up,” Cooper said.

“The Gulf War had just finished, and I did a caricature of Saddam Hussein on a prayer mat praying with a couple of spent cartridges smoking next to him.

“It was when the allied troops had gone through Kuwait and they were deciding whether to go into Baghdad and finish him off.

“They had an article in the paper titled ‘Saddam, what now?' and the editor just rang me and said, ‘we've just got your caricatures, and this one of him praying on the mat is perfect'.

“Next thing I know, I'm on the front page of the national newspaper, but I couldn't get a job apart from standing nude in front of an art class.”

“It was all to do with art, in one way or another, but my full-time work was cleaning toilets in a factory. That was the only other proper job I could get.”

A return, a revelation and rewards

In spite of his work previously adoring prime real estate in the Danish tabloids, Cooper was yet to crack it in his homeland.

“After coming back from overseas, I just wanted to paint,” he said, leaning on the armrest of his studio's couch.

“So, I was doing portraits of friends and working in a bar just trying to make ends meet.

“For three years, I just worked in a bar and painted.”

However, after recalling the timeless pieces he laid eyes on his jaunts throughout the great galleries of Europe, the footballer come janitor come barman had an epiphany.

“I always thought in the back of my head ‘the sports stuff would be great to paint'.”

“You go to all of those galleries around the world, and you see all of those Rubens, and all of these classic paintings of the angels going up through the clouds.

“I thought ‘well, that's a pack of players climbing up in the afternoon light with the dark grandstand behind them, and it almost looks biblical'.

“I thought ‘I'll just do one and see how it goes.'”

In the same season that his former club died a bitterly depressing, and very public, death, North Melbourne were awarded their fourth premiership, and thus far, the league's only golden cup.

But for Cooper, when the Kangaroos were cavorting on the dais after trumping the Swans, another lightbulb went off in his creative mind.

“I did one of the 1996 North Melbourne Premiership and they were all up on the podium. There wasn't one photo where you could see all of them, so I merged a few together and made one.”

“Someone made me an offer to buy it, but it was about a quarter of the price that I wanted, so I said, ‘bugger it, I'll keep it'.

“But the club said, ‘we could reproduce it and sell prints to the fans' and asked ‘have you got a license with the AFL' and I said ‘no, what's that?' So, I ended up putting together a business plan and taking it to the AFL to be a part of their memorabilia program, which is what I have been doing for 20-years now.”

SEE ALSO: Over 300 players nominate for AFL Mid-Season Draft

With a skillset, product and a model both behind and in front of him, Jamie Cooper: Sports Artist was born.

The commissions began to roll in, including the commencement of a series that would see Cooper stake his claim as the best artist within the niche genre – his legendary Team of the Century paintings.

“It was the late 1990's, and I had done a couple of jobs at Collingwood and one for Garry Lyon's retirement, and then the clubs were all announcing their Teams of the Century, I thought ‘that's perfect to paint' because you can't get that scene, as it doesn't exist,” the artist explained.

“The only way to get it is to recreate, and the best way to do that is to paint it.

“Photoshop was just starting, and I remember Carlton were going to do a team photo with all of the heads stuck on, but it was like someone from 1920 stuck on a modern-day frame.

“It looked so stupid.

“I said ‘I can paint that for you, but I can also put them in the changerooms for you'. So, Serge Silvagni and Steve Silvagni are having a chat in the corner, and it was made to look like it was believable.”

For anyone that has ever laid eyes of any of Cooper's ‘dream scenes', you will know that the addition of historically based ‘Easter Eggs' within his work have become his signature. The introduction of these visual homages came after an exhaustive period and some libation with friends.

“The first one I think I did, the one for Carlton, I wasn't even thinking about ‘Easter Eggs' then, I was just trying to put the players together.”

“Then at the end of the painting, I was sitting back with a couple of mates having a beer thinking ‘I wonder how this is going to go?'

“Then someone goes ‘You should have a dead Magpie in there as a joke' and I thought ‘that's a great idea!'

“I had all of the premiership cups on top of the lockers, so I thought maybe I could have a magpie hanging out of the 1970 cup, but then I thought that might be a bit too graphic.

“Bruce Doull was up the front, sitting on the rubdown bench and had his foot on the ground. So, I put some feathers coming out from underneath his foot.”

With the piece complete, and Carlton keen to display his wares on prime-time television, Cooper was given a professional ‘leg up' from an unlikely ally – the ever polarizing, Sam Newman.

“They showed the painting on ‘The Footy Show' and had a chat through it all, and Eddie [Maguire] said, ‘there's a limited edition prints from the club, so ring in now and get them'.

“They went to a commercial and then came back, and they've said, ‘the guys out the back have just noticed something.' And because I didn't say anything about the Magpie, Eddie goes ‘those mongrels at Carlton!'

“They've brought the painting back out and Sam Newman said, ‘check this out, there's a squashed bloody Magpie under there' and everyone was laughing. That's when Carlton reckons that the phones started going crazy.

“They sold a thousand prints in a day.”

Although these often-undetected instalments are small in size, the man whose brushstrokes include them believes that they are as important as the players that dominate the scenes.

Cooper has also used them as an opportunity to both self-promote and settle scores.

“I've got myself holding up the banner in my overalls in the Fitzroy one,” Cooper said.

“In Richmond's, I gave Dale Weightman a black eye because he king hit me from behind one day.”

“It was probably only my fourth or fifth game and I came off the bench. It was probably one of the first touches I had, and I was just tapping the ball along trying to pick it up, and he just came up behind me and went whack!”

“We'd already lost two players to hamstrings, So I had to stay on for the rest of the day.

“I literally didn't know when the half-time siren went, as I was standing in the middle of the ground looking at the light on top of the grandstand thinking how nice it was. I was just away with the pixies; I had no idea where to go to get off the ground.”

“That was just me getting him back for the knockout. The brush is mightier than the sword.” Cooper pontificated alongside another chuckle.

In the decades since these hyper-realistic masterpieces have found their way onto the walls of football clubs across the nation, Cooper has once again taken his talents back across land and sea.

Should you visit many of the famous round ball cathedrals in Europe, you are likely to meet fanatics that are familiar with the 56-year-old's brushwork and hidden larrikinism.

As the only known member of the human race that has held a working contract with mammoth organizations such as Manchester City, Liverpool, Chelsea, Leeds United, Real Madrid, as well as Major League Baseball franchise, the Philadelphia Phillies, it is clear that Cooper is the global leader when it comes to meshing the past with the present.

Even if the procedure of putting them together is a painstaking one.

Projects and process

Having concluded our walk down memory lane, my eyes once again surveyed the studio around us.

Since walking in, and composing myself at the feet of the gargantuan representations of Australian sporting royalty, I couldn't help but become transfixed by the canvas that sat across an easel away from the windows.

Although almost complete, Cooper explained that a veil still remained on his latest project. However, when prompted, the painter was quite happy to inform me of its significance.

“I'm doing Richmond's back-to-back premiership team,” he said.

“It's an on-field, imaginary final whistle moment. It is supposed to represent that moment of pure celebration.

“I've put the players in poses that reflect when that siren sounded, because that is ‘the moment' for a footballer. That's when it all sinks in. All of the relief and the ecstasy.

“They're all there on the MCG/Gabba and it will have confetti and streamers going everywhere. It will be a real party atmosphere.”

As the soon to be completed project still showed signs of grey lead, sticky tape and a fragment of free space, I wondered aloud about what the process was when it came to completing such an intricate scene.

Cooper explained that although the painting process was what would eventually secure attention, the bulk of the task is already completed before the canvas is even stained.

“A lot of the work is done before you even pick up a brush,” he explained.

“If I am doing a historical piece and creating one of these scenes that doesn't exist, I've got to compose ‘who is going to be where and what are they going to be doing'.

“Then once I have decided what angle they are going to be on, if two guys are going to be communicating with each other and they are sitting down talking, I've got to find a photo of their head on an angle that looks natural to be talking next to them.

“They can't all be standing there looking at the camera and smiling like they would most of the time in team photos.

“So, I go through the archives and try and find a photo of them doing that, and if I can't find one, I have to get a model to sit and be their body. Then I'll put that in photoshop and stick their head on the body and make it look right, before pasting it all together in a scene with everyone in the right spot, on the right angles, with the right perspective.

“That takes about four to six weeks.”

Pencil sketches, back and forth consultation, projection and painful finicking then ensue, before finally the familiar figures are brought to life with brushstrokes.

From ‘go to whoa' on a project of this size, Cooper often needs to dedicate a large portion of a calendar year.

“For the big team ones, probably four to six months, and that's cramming it in!” he explained.

“That's why there's not many people doing it, it's a total pain in the arse.”

Although tiring, it is undeniable that in merging his pair of life passions, the former Lion has created a special place in the game, even though his boots have been collecting cobwebs for over three decades.

For this, he can be proud, as for many former footballers, the ambiguous road away from clubland has swallowed successions whole.

Musings, advice and individuality

To complete our conversation, I asked Jamie about what his regimented football career had taught him, and how he had applied that into his second calling in which the shots were his alone to fire.

“One was just understanding what a club means," he began.

"Which anyone that has played footy knows what that means. It doesn't have to be AFL or VFL, it can be any club.

“I played football all my life, so I really understand what a club means to the fans, and I also understand the feelings of the players and the moments that are important. That helps me choose my moments when I paint and what images I choose.

“I also understand the story of the painting that connects with the fans, because I was a fan when I was a kid, I used to love my favourite footballers. There were moments in their career that I would never forget, so I guess I have the angle of the artist and the athlete – which helps.”

Although he has managed to master this when it comes to his native code, Cooper explained that the scrutiny surrounding minutiae intensified when working with foreign clubs.

“Even if I go to foreign countries and do cultures that I'm not familiar with, I understand the importance of them – that's why I do all of the research because I know how important it is.”

“If you get something wrong, especially in England, they'll cut you to pieces. So, you really have to respect that.”

Apart from this sense of togetherness, Cooper elucidated that the individual lessons he learnt in his twenties were still aiding him in the present day.

“I'd also say just believing in yourself, and trying to get better all of the time, as well as not worrying about rejection. When you are playing footy, especially at the highest level, you get really criticized.”

“If you do something wrong, you get told in front of everybody, but if you do something good, you also get told in front of everybody.

Maintaining ones temper and sense of self was also paramount according to the dream scene constructor.

“You have to be really objective and not get too caught up in yourself, because some players would crack the shits when they got criticized, they couldn't hack it and their careers ended because they couldn't deal with it."

“That was a really good lesson because when I go to a really big football club and present to them in a boardroom in front all of these old people, I have that experience of being able to stand up and say ‘this is who I am and this is what I do' – I'm be able to fight fear.

“I'm afraid of the rejection, but it doesn't stop me.”

As his former club are no longer an entity in the game's highest grade, the 26-gamer explained that his connection to the game remained strong in a professional sense, but that his heart was that of a vagrant, in that it had nowhere to hang it's hat.

“I still love footy,” Cooper said passionately.

“But because I do work with lots of different clubs, I feel like a bit of a nomad because I don't really have a football home.

“If Fitzroy was still Fitzroy, I would be 150% Fitzroy, because I was there and I was a part of it. It was incredible.

“But they're not Fitzroy anymore, and even though I've got nothing against Brisbane at all, in fact I still sort of barrack for them, but you can't pretend you love it – you either do or you don't.

“Some people could just go straight across to Brisbane and continue on, and some people could never watch a Brisbane game because they're too cut about Fitzroy, and I totally understand both sides – I'm sort of somewhere in the middle.”

The masterpiece maker then pondered briefly before heralding a theory that espoused his two lives.

“I'd like to be devastated and elated, that's sort of what all of these paintings are about. If nobody really cared that much, nobody would care about the paintings that much.”

With wisdom and a power of work behind him since his red, yellow and blue guernsey was replaced with paint spattered overalls, Cooper had these words for players who may feel that their career were cut short or were fearful about what was around the next corner.

“All you can ever do in life is follow your joy or follow your bliss, whether that's footy or whether it's art, whether it's both or whether it's something else,” he said.

“I would just say ‘if you love it, do it'.

“I would also say ‘never give in and never give up'. Keep looking for what you love. If you don't have anything outside of football, spend your life trying to find out what that is.

“Never stop.”

As we parted ways after a few photographs and some local weather advice, I once again shook the hand of a man that could create beauty in our game – even without possession of a leather ball.

With my shoes again muddied as I walked through Jamie's gate and into the chilly breeze that chicaned through the gum leaves above me, I was content in the knowledge that when one door, window or gate closes, another will eventually open.

But only if you want it to.

Should you wish to get in contact with Jamie or simply browse his work, you can do at his website, his Instagram or his Facebook page.