Should you pour through the annals of recent history, it is clear to see that 1995 was a year marked by the creation of many connections on Australian shores.

Outside of the green seats of the House of Representatives, freshly minted opposition leader John Howard reached out to Labor's heartland voters with an outstretched hand and a promise to hit the election with their values at heart.

In the boardroom, Qantas waved goodbye to the strictures of the public sector to then walk arm in Armani-clad arm with the high-rollers of the private world.

And on the playing field, rugby league icon, Ian Roberts, proudly became the bridge between the beer-swilling sporting world and the glitz of Sydney's gay scene.

In Sherrin-spiraling territory, 1995 may be best remembered as the season in which Carlton became connected with their 16th premiership cup, but it was also the year in which Australian Rules Football and Rock'n'Roll collided head-on in the south-east of Melbourne.

While their debut at a quaint suburban venue was in step with almost every band that has ever had a record pressed, the rise of alt-rock act TISM (This Is Serious Mum) had reached its zenith by the mid-90s.

As a prolific producer of tunes since this inaugural gig at an athletics track in Melbourne's south-east, the group renowned for their loaded lyrics, searing 'piss takes' and being more cutting edge than a Jarrod Brennan bounce had begun to gain a cult following.

With their everyday identities concealed by both costumes and comic pseudonyms, an ability to say what they wish - without reproach - was found, and, in turn, the capability to cut through all of the pap getting radio play.

Routinely found in close proximity to a copious amount of VB cans, TISM's true strength was their ability to mix high and low-brow culture well before merchant bankers took to dressing like tradies outside of office hours.

Yet, while their shows would routinely be packed to the rafters with the most raucous members of the rank and file, it wasn't until the collective took off a timeless TAC television ad and took down a Hollywood heartthrob that the heights of mainstream success were hit.

With tracks such as ‘Jung Talent Time' and ‘What Nationality is Les Murray?', TISM's third studio album ‘Machiavelli and the Four Seasons' was punctuated by punches thrown - up, down, left, right, and centre - at every cornice of Australian culture.

Released on May 4, 1995, the Platinum Studios press went gold to see the previously unheralded group acclaimed with an ARIA – collected by none other than Les Murray on their behalf - and a pair of tracks earning top 10 status of Triple J's Hottest 100 that year.

But while the band who had begun life in Murrumbeena Park were thriving, the footy team at the other end of East Boundary Road was clinging on for dear life.

Cultural cross-pollination

By early May of 1995, the St Kilda Football Club were rapidly approaching a 30-year break from premiership success and remained rooted to the bottom of the 16-team ladder with no wins from six outings.

These losses on the field were compounded by the addition of more off it, with the Saints' financial sins no secret to anyone with an ear to the wall, and an eye on the times.

While the Moorabbin-based side would eventually haul themselves from the cellar by claiming eight wins before season's end, perhaps it was a left-of-centre training session that amplified the Saints' run home that winter.

Given the lyrics, “The guy who slagged the football team, those yobs were not for him”, it's clear that TISM's hit track ‘Greg! The Stop Sign' doesn't so much chart the lives of those in the locker room, but instead spins a tale of mortality.

Still, for fans of the band - and ardent viewers of Rage during the 90s - the link between the game and the tune is vivid, given much of the film clip was filmed within the bowels of St Kilda's Moorabbin home.

Close to three decades have passed since a quartet of Saints – Shane Wakelin, Josh Kitchen, Chris Hemley and Justin Peckett – traded training for roles in front of the camera, so it remains strange that little has been asked of this piece of cultural cross-pollination.

So much so that while St Kilda's involvement in this time capsule moment has been stamped forever, many involved in the process have no recollection of how the connection between band and club came to pass.

When speaking to Zero Hanger, Peckett himself revealed that while the advent of the event was a bit of a mystery, the 252-gamer was over the moon to have received the call-up.

“The club asked a few players if they would be interested, and there weren't too many takers, but I put my hand up straight away,” the defender delineated.

“I was the only one at the club that really appreciated the band and their music. So, it was quite a thrill, but for everyone else, it was probably just a pain in the arse.”

Dressed as though they were fresh off a bank heist, TISM raised eyebrows within a changing room that had once been home to the likes of Baldock, Barker, Burns, and Breen.

And, despite their rambunctious reputation, Peckett held the view that it certainly hadn't preceded them at Moorabbin.

“I would doubt that they would have known much about TISM and the content behind some of their songs, but they were clearly open to having them there,” Peckett said.

“At least one of the band members was a mad Saints fan, so he may have had a connection somehow, and maybe he painted a picture that they were some ARIA Award-winning, top 10 Australian superstars, and the club maybe jumped at that.

“I would doubt the club would have known too much about who they (TISM) were.”

While holding a CV that was far more 'Hollywood Boulevard' than Linton Street, acclaimed film director, Mark Hartley, was calling the shots behind the camera that evening.

And while he too couldn't put a finger on who pulled the trigger on the project, the long-term band associate agreed with Peckett in that it was a love of the league's leading sinners that led his crew south of the CBD.

“All I can remember is somebody in TISM was a mad St Kilda supporter,” Hartley explained.

“So, we went to the club and said, ‘will you let us shoot a music video in your clubrooms? And we will try to promote St Kilda as much as we possibly can'.

"Remarkably, they agreed.”

Sources close to the band shared this same view to Zero Hanger, but with a desire to maintain their final shroud of anonymity, the true catalyst for synth tunes and Sherrins colliding is set to remain masked for the time being.

Although admittedly hazy with much of the minutiae, Hartley did recall that for a band containing published authors and an English teacher, one particular mishap was still crystal in his mind.

“I do remember the band were very taken by the fact that some of the inspirational slogans around the changing rooms at Moorabbin actually had spelling mistakes in them,” he said with a chuckle.

Even though no parties were keen to take ownership for the project's proposal, with St Kilda's books containing more red in those days than their current clash strip, it appears likely that the band with Saintly ties were simply answering a distress signal.

Battles, Blues and boardroom wolves

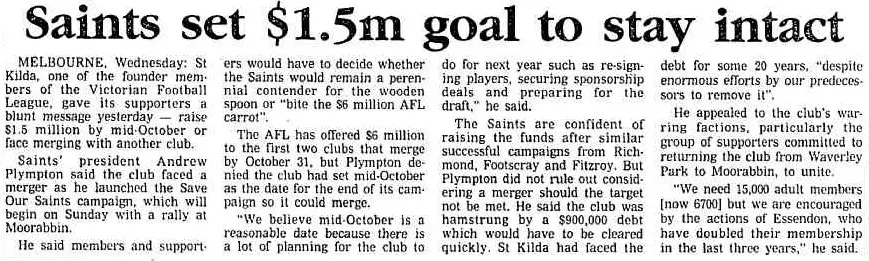

The day after his side fell by 17-points to the Demons midway through 1995, Andrew Plympton told the footballing world he could no longer keep the wolves from his boardroom door.

As the president of the struggling Saints, Plympton had been working feverishly to provide off-field stability to head coach Stan Alves and his now Tony Lockett-less lineup. Yet, by the close of business on Monday, June 26, 1995, the administrator was finally forced to send for help.

Plympton's call to create the ‘Save Our Saints' fund was made to draw the club's latent fanbase back to the bleachers at Waverley Park, and to make sure their wallets came with them.

“The move of doing the ‘SOS' enabled myself as president to say to our members in a very open and honest manner that I couldn't guarantee our future,” Plympton told Zero Hanger.

But if those jaded by the bevy of wooden spoons ‘won' since 1966 could not be swayed, the prospect of destitution would have certainly become a reality.

“Behind closed doors, this was a time when the AFL was very much suggesting that there were too many teams in the competition. This was also a time when all clubs were talking to each other in regard to mergers and relocations,” Plympton continued.

“There was a high level of uncertainty in the marketplace, and we were all, somewhat, unsure where we were all headed. The bottom line was that we [the St Kilda Football Club] were vulnerable.”

With a balance sheet that resembled a one-man-operated seesaw and a football department at odds with the social club, the situation was so dire that routine conversations with Carlton president John Elliott about a merger were held just to keep the haloes above water.

“I spent a long time working with John,” Plympton revealed. “But [the prospective merger] was derailed when Carlton went through the '95 season only losing two games.

“It was their 15 premierships versus our one premiership, so people would then have suggested that St Kilda would have been at a distinct disadvantage. But the answer was that we weren't because the AFL had stated that if we were to have succeeded with the Carlton Football Club, there would have been substantially more funds available to both of us.”

However, contrary to past reports which have suggested the club's jumper, ground and history would be cast aside, the man at the Saints' helm claimed nothing beyond the preliminary was ever raised.

“We never spoke about things such as colours and who was going to be on the list, it was more about the purpose and how the competition was going to end up,” Plympton added.

“It never got to a stage when we'd agreed on anything, but it was certainly an interesting background and a position that the board gave me full support to go and discuss opportunities with Carlton.”

Throughout the remainder of the 1995 season, the importance of the scoreboard had taken a backseat to the Saints' fight for survival.

Loose change was collected in the grandstands and greater donations came in from those with deeper pockets, but it was the maneuvers of Plympton and his board that set the wheels in motion.

“We had this company called the ‘St Kilda Saints Limited', which was a non-listed, public company,” he said.

“We managed to go and speak to all of the shareholders of the company to persuade them to donate all of their capital back to the club, and all of them agreed. That gave us a $260,000 start to get the process of ‘SOS' underway.

“My memory is clouded, but we probably raised about $600,000 overall and with the hard work of a lot of people, thank god, we got it done because it saved the Saints.”

Almost 30-years on from his commandeering role in keeping his childhood club on the park, Plympton's sentiments remain as true as ever.

Still, it wasn't just the efforts of those in suits and ties that saved the Saints.

There was still a part to play for those in balaclavas too.

The Big Day In

For those with anything close to a keen eye, the St Kilda Football Club has always had a tight relationship with those adept with a plectrum.

Rockers like Dan Sultan, Ross Wilson and Tex Perkins have never been shy in amplifying their faith, and industry string-pullers Michael Gudinski and Molly Meldrum will always be known for their utter devotion to the red, white and black.

Yet, while Molly was a routine spruiker of the Saints' wares each week on Countdown in the 80s, this affiliation between the sporting club and noted stage acts had hit a lull before TISM showed up in the winter of 1995.

And irrespective of the fact that St Kilda's crest, colours, and still erect grandstand were thrown back into the cultural consciousness, the group of anonymous stirrers weren't content to stop there, especially when there were funds to be raised.

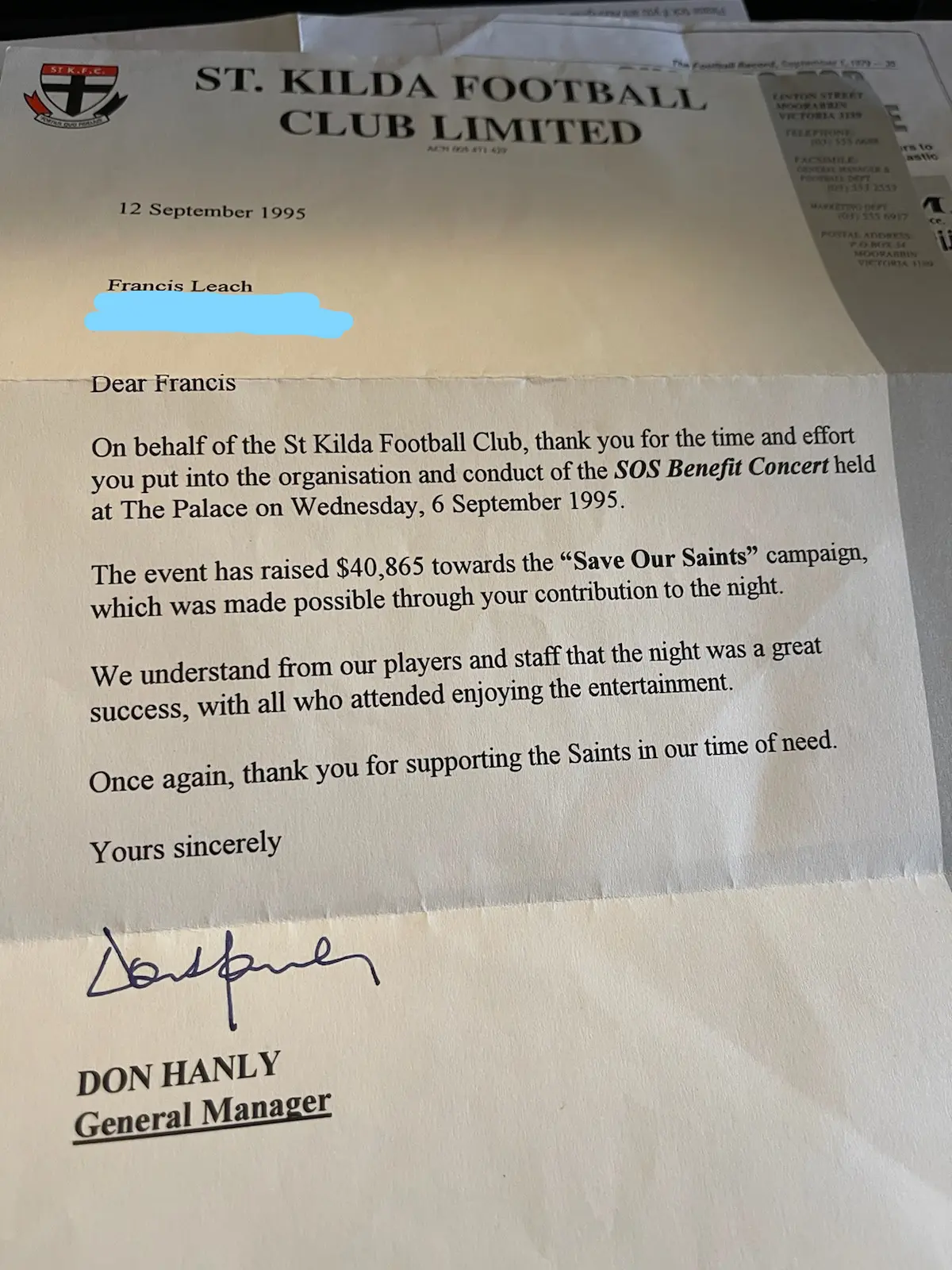

Across his myriad of years in the public eye, Francis Leach has worn many hats. Run a rule across his resume, and you'll find the polymath is as adept behind a microphone as he is with a quill in hand.

But in 1995, the man with a self-confessed love of ideas had possibly his brightest yet when he decided to save the Saints through song.

On Wednesday the 6th of September 1995, as the club's playing list were likely still nursing hangovers from their recent Mad Monday celebrations, St Kilda's version of The Big Day Out took place just a Jeff Fehring spiral from the Junction Oval, at The Palace on Jacka Boulevard.

With a veritable ‘who's who' such as veteran pub rockers ‘Cosmic Psychos' called on to pick up a pick and strum for the Saints, Leach explained that the benefit gig came together without a hitch.

“I remember a good friend of mine, Mick Newton, was working at Premier Artists at the time. We were both heavily involved with St Kilda at the time and thought, ‘what can we do?'. The one thing we could do was get our mates together and play a gig,” he told Zero Hanger.

“We immediately got in touch with our friends in the music industry and just went from there. In the end, we pulled together an incredible lineup - it was like ‘The Big Day In'. We picked the eyes out of the best that was available and just asked them to play for nothing, it was great!”

Having stuffed the entertainment complex full of paying patrons, the crowd of punks, rockers, sinners, and Saints players was treated to a traditionally chaotic TISM finale.

“With TISM, I had known their manager, Michael Lynch, for a very long time and I knew through him that they were football fans,” Leach added.

“We just spoke with him, and the band instantly said they were in, which was great because it was just a superb way to finish the night.”

Despite proving able to rake in $40,165 (or just shy of $75,000 in today's terms) to prop up a football club that has almost exclusively caused him despair, the passionate provisioner also managed to live out a boyhood fantasy by pulling on the club's colours just days later.

“There was also a charity game that we played down at Moorabbin a few weeks after the concert, which pulled in about 10,000 people on a Friday night,” Leach claimed.

“We played, and it was a lot of fun. I'm sure I've got photos somewhere of me wandering around with my shocker of peroxide blonde hair in a St Kilda jumper. I was living the life.”

Born a pair of years after St Kilda's lone premiership success, Leach, like almost every other member of the club's congregation, is still waiting for that one afternoon in September when his prayers will finally be answered.

And although his connections between the structures of the footballing world and those that sing for their supper kept this dream alive, with three grand final losses (and a draw), two wooden spoons, and a galaxy of false dawns arriving since 1995, this choice to divinely intervene is sure to have been questioned from time to time.

Throughout the century and change of league football history, clubs have both come and gone, with each of those still standing familiar with what the wall feels like on their backs.

When looking at these clubs that will continue to add to their annals in 2022, their saviours have come in many different shapes and forms.

For the Hawks, Demons, and Bulldogs, it was their fervent fanbases that kept their clubs rolling. In the case of Fitzroy, there were hopes that an island made almost entirely of birds**t would lead the Lions into the 21st century.

But for St Kilda, it was an ardent administrator, a bottle blonde, and a balaclava-clad band that kept the Saints marching in.