“What my grandfather said is to get a tune out of a piano, you can play the black notes, and you can play the white notes. But to get harmony, you've got to play them both”

– Sir Doug Nicholls

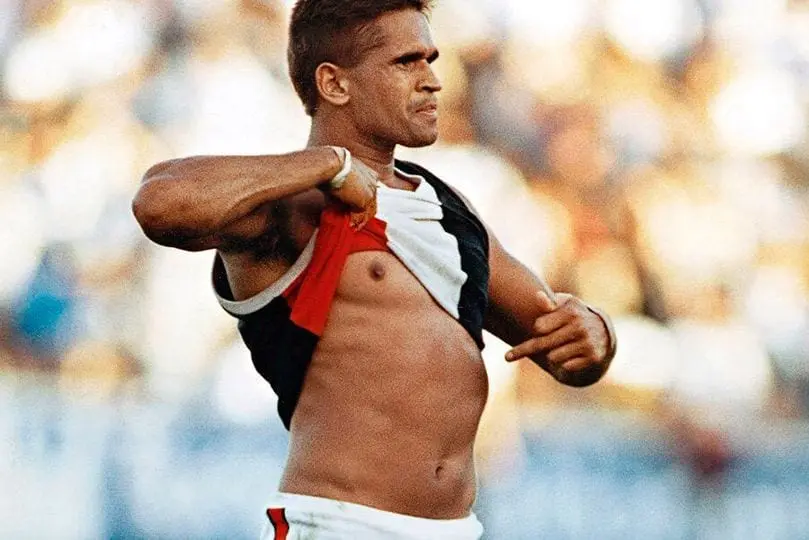

Through fading April light, a cocked middle finger from a taped left hand pointed at a full set of abs. The right hand, also bound by strapping, held a red, white, and black jumper aloft, bearing a black torso defiantly toward the Sherrin Stand.

This brave show of strength was not rewarded. The parochial home crowd was not impressed. With a cyclone of spittle, they jeered as the jumper was lowered and kisses were blown back across the boundary line.

The lone sharp key on a board of ivory, Nicky Winmar was making his stand.

“I'm black and I'm proud,” he said then, just as he says now.

Mere metres away, Winmar's teammates hugged and shrieked at the top of the caged race. For them, the moment represented the end of a sorry losing streak after slotting 18 goals - all, mind you, arriving without the services of the game's greatest spearhead.

For Winmar, the same had been true enough at first. But in the minutes, hours, years and decades to follow, St Kilda's win over Collingwood - the Saints' first over the 'Woods' at Victoria Park since 1976 - came to represent so much more.

So much of it in direct opposition to those that ran out beside him.

Those racist Pies fans may have felt powerful as they fired phlegm and barbs that dying day, side by side, from the safety of the outer, but Winmar claimed his power back.

The lone sharp key on a board of ivory, Nicky Winmar had made his stand.

Almost 30 years to the day, Winmar was back at the scene of the crime, seeking to close wounds that were never left to heal.

By way of a healing ceremony at Victoria Park on Tuesday night, or Ngarra Jarra Noun (Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung for healing), the 57-year-old made his stand once more.

Only this time, hundreds, if not a thousand, stood with him.

Faces from all races converged on Victoria Park through fading April light, using the gathering to heal together, as well as reflect on their own actions and attitudes towards First Peoples.

Of the tight throng that gathered around that same caged race, most were clad in t-shirts bearing a younger Winmar's image and the older man's handprints, the profits of which will go to the St Kilda Football Club's 'Point and Be Proud' program.

Out in the pocket, the legendary Saint was joined by former teammates Gilbert McAdam, Dale Kickett, and Jayson Daniels. On-field foes, now off-field friends in Michael Long, Byron Pickett, Des Headland, Leon Davis, and Jeff Farmer were also alongside.

From the old school, Robert Muir had made his way across the border, the bespectacled 69-year-old standing shoulder to shoulder with Joel Wilkinson and Héritier Lumumba, the latter making an even longer journey to be there.

Current-day Collingwood captain Darcy Moore and president Jeff Browne were there to play their roles, observing quietly after their club's belated apology issued at the weekend.

Around a pair of fires, smoking high from the feed of green gum leaves, dances were performed, stories were told and songs were sung together in shared healing before the same Sherrin Stand.

Nicky Winmar and Richard Walley join in the spirit dance at tonight’s Black & Proud event at Victoria Park ❤️ pic.twitter.com/Cj3GGd8oW2

— AFL (@AFL) April 18, 2023

A long way to go

To say Australia - and its many people - aren't perpetually caught in an identity crisis, would be to peddle a serious mistruth.

Whether you grew here or are new here, the point is moot, as collectively, this country and its people often don't see themselves honestly, even on its greatest equaliser: the sporting field.

Anti-authoritarian. Egalitarian. Laid-back. The land of the fair go.

Australians have long spruiked a set of values that are held close to heart. Values that are said to be representative of all. But when push comes to shove, these values are often nowhere to be found, leading the same victims to wonder whether they ever existed in the first place.

Though this peg-back isn't representative of every individual, with the good eggs - more often than not - outweighing the bad, time and again, it is these bad eggs that serve themselves to our First Australians, even those on our most beloved stage: the sporting field.

When Lionel Rose beat Masahiko 'Fighting' Harada for the world bantamweight title in February of 1968, the Gunditjmara man may have already blown out 19 candles on his cake, but he had only been seen as a fully-fledged Australian for nine months - a heinous wrong only righted by referendum.

And though thousands would rush out to buy the multi-talented fighter's album when it hit shelves in 1970, just as hundreds of thousands had bolted to parades around the country to welcome him home from the Harada bout, the praise wouldn't last.

Like Rose before him, Winmar's canvas - the footy field, rather than the ring - provided little sanctity from racial abuse. Like Rose before him, Winmar would have to keep his hands up.

Since Joe Johnson pulled on Fitzroy's maroon and gold in 1904, Indigenous Australia has had a big-league representation. And though Winmar would become the face of change following his stand on the big stage, the proud Noongar man from the Western Australian Wheatbelt region was not the first First Nations footballer to be struck with racist slings and arrows.

Even the man the game hails for a fortnight each year, Sir Doug Nicholls, was targeted, seeing his brief time at Carlton during 1927 conclude after experiencing abhorrent racism from would-be teammates and trainers.

Though posthumously forgiven, these ills would not be forgotten by Nicholls during his lifelong fight for equality. A fight that took him all the way to the South Australian Governor's office.

A Saint-turned-Bulldog, Winmar is not the last name from either club to be debased by hate, with contemporary Saint Bradley Hill speaking on the abuse he received during his second year with the club before a young Pup took matters into his own hands less than a month ago.

Across the past 30 years, singular moments of reconciliation are often lauded as signposts of wider healing, with the words 'look how far we've come' routinely staked in the ground.

Still, we all got a stark reminder of the truth when Jamarra Ugle-Hagan was forced to lift his own guernsey and make his own stand.

Ironically, the then 20-year-old's homage came as those on Capital Hill needlessly debate a referendum to allow First Nations people a voice, not just the chance to be counted.

Racially abused by a still unidentified 'fan' during the Bulldogs' Round 2 loss to St Kilda, Ugle-Hagan took time from the club to heal with his own, bravely returning less than a week later to beat Brisbane with five goals from his own boot.

“I did want to make a stance. I wanted to show my presence," Ugle-Hagan said after the final siren, unsuccessfully fighting off tears.

“I'm just a boy trying to play some football – same as the other indigenous boys – and just be strong.”

Post-game, the young forward sat alongside his coach, Luke Beveridge, with the seasoned steward offering both balm and a challenge to those in footy circles, as well as those from further reaches.

"We've got to dance with them," Beveridge, a former teammate of Winmar's, stated.

"When you consider across the ditch what New Zealanders do and how they connect with the Māoris and the Polynesians and everyone from the islands, they touch foreheads, it's such a connection

"We haven't established that yet."

And though Beveridge, too, would utter familiar words, they would come with a caveat.

“I think we've come a long way since ‘Cuz' (Winmar)," he said. "But as much as we have come along that way, we've still got a way to come.”

Australians may like to think of themselves as a laid-back nation of suntanned larrikins, but the question remains: just how laid-back is racially abusing a 20-year-old in what is, for all intents and purposes, his office?

Time and time and time again

As a straight, white male, standing on the receiving end of a racial slur is as foreign a concept as walking to or from Shabbat services or the pangs felt from Ramadan fasting.

But as a living, breathing, voting Australian, with a heart, a soul; open eyes and ears, I am, as are many others, aware of how it makes victims feel. Why? Because they keep telling us all, time and time and time again.

Since Ugle-Hagan's well-received stand, at least four of the AFL's First Nations stars have gone public with vile racism they have received. Izak Rankine, Michael Walters, Nathan Wilson and Charlie Cameron.

Four in less than a month.

While these stars, both rising and solidified, have joined Ugle-Hagan on the frontline of the fight, a report from The Age this week claimed that 23 reports of similar prejudice have been made to the league's office this season alone. Buttress this with News Corp's expose that only 10 memberships have been cancelled since 2019, and it is clear that more needs to be done.

Upon hanging up the boots after 350 games and 640 goals, Carlton and Adelaide champion Eddie Betts claimed that the AFL was not a safe environment for Indigenous players. And despite receiving a thunderous welcome back to the fold during Essendon's Round 1 win, it's worth remembering that Anthony McDonald-Tipungwuti's hiatus began after being racially abused.

Both Betts and 'Walla' have songs written about them, with each causing more fans to leap in the stands than just about anyone that has come and gone since. These two are said to be the players that everyone loves unconditionally, or is that just another story we tell ourselves in order to live?

Carrying the fight

On the night he lifted his jumper and stood his ground - only hours before his stance was printed onto front pages and spread across the city - such were the fears for the star's safety, Winmar was forced to hide out at Molly Meldrum's home in neighbouring Richmond.

Time may have elapsed since that April afternoon, but unlike Jamarra, Australia wasn't yet mature enough to let an Indigenous man have the final word.

People who battle injustice never come out unscathed. They carry the fight with them every day, even after belated apologies are extended.

After hanging up his own boots following a single season at the Whitten Oval, Winmar's life has been colourful, to say the least. Following several amateur footy appearances across the country, he worked in construction, as a shearer, and in the mining industry. Ill health and misdeeds would find him, with a heart attack in 2012 and a pair of assault charges arising.

Now a grandfather, the 57-year-old has stepped out of the light, finding alternative therapy by way of paint and canvas. Two parts icon, one part Jackson Pollock, Winmar's brushstrokes were exhibited on St Kilda's most recent Sir Doug Nicholls Round guernsey.

For 30 years, it has stuck with him. For 30 years, it has hurt. But for nearly 60 years, the Hall of Famer has held his head high.

Still black. Still proud. Still with a love for the Saints.

A scene to be believed

Such is the illusory connection between supporters and superstars, certain Saints fans have often acted as if they too own Winmar's moment.

In their eyes, his stand is a moment they both shared. A collective 'up yours' from both parties to Pies fans everywhere, even if many on the outer haven't twigged to the message at all.

As a white bloke, I have heard many racial slurs fired off in my presence, with some around me holding the misguided belief that because I look like them, I must think like them.

Never have I heard more of this abuse than in my years attending AFL games.

For much of the past half-decade, two mates and I held reserved seat memberships for St Kilda home games at Marvel Stadium. During our first year, we all sat in the pocket of the La Trobe Street end and were rewarded with an unimpeded sightline down the ground.

While the view was great, the atmosphere wasn't, with the little bald man and his heavily pierced son sat behind us routinely shouting out slurs. Complaints were made to stadium officials, but routinely fell on deaf ears.

Every single week, this pair would spit hate at opposition players, yet laud the likes of Ben Long, Jade Gresham, and Koby Stevens.

Funny, that.

Eventually, the three of us moved around to the city wing. But while the patrons around us may have changed, the same bullshit remained.

Ahead of St Kilda's Round 11 win over North Melbourne last season, Winmar and his cousin, Fabian Winmar, played a didgeridoo duet to mark the opening of the latest Sir Doug Nicholls Round. A fixture in which Winmar's Saints would be wearing his artwork.

While the vast majority of the crowd watched on respectfully, the sour cries of a bitter geriatric could be heard on centre wing. The perpetrator? A hunched octogenarian with clearly no love for the performance - or the performers - until the big screen showed a crystal-clear shot of Nicky Winmar playing his instrument.

'Nicky!' he cried, changing his tune on a dime. 'Go, Nicky!'

Funny, that.

As a younger man, this plaster Saint probably stood by the picket fence at the Junction Oval, moving on to a favourite spot at Moorabbin, and a wooden perch at Waverley before adapting again to life under the Docklands roof.

With white hair and a murder of crow's feet, he has seen plenty of change. Players. Coaches. Jumpers. Governments. Laws. Maybe he was there that afternoon in September '66. Maybe he voted in the referendum two years later.

But now, rug on lap, cane in hand; bitter of heart and blinker-eyed, he is left clinging. Clinging to distorted memories of familiar faces. Faces that stared his sort down 30 years ago.

The world has changed; as has the game. Adapt and advance, they say, or stay rooted and, well, rooted.

A certain sect of St Kilda fans seems to believe Nicky Winmar belongs to them, and that his message was one sent directly from them to the eyes and ears of Magpie fans everywhere.

But if you're anything like the short, bald man who sat behind me, his heavily pierced offspring, the geriatric with the adolescent petulance and the tunnel vision, or the still-faceless ‘fan' who fired off at Ugle-Hagan, Winmar's message wasn't from you, it was for you. A message that you still haven't heeded after far too long.

Your side may have won that April afternoon at Victoria Park, but you are on the wrong side of history.

Every key in harmony

"I'm black and proud," Winmar called out to the Victoria Park crowd, one that looked decidedly different from that afternoon 30 years ago.

The Magpie men don't play at Victoria Park anymore. They haven't this century. The ground is home to the women's team these days and their accepting alternative crowd. During the week, the once hostile surrounds play host to adopted greyhounds, walked by folks in Gorman jackets sipping oat milk lattes.

Things have changed here. Changed for the better.

Through song, dance, and story, Winmar and his inner circle healed before this welcoming crowd. But while all there were in step to the beat of the same sticks on Tuesday night, riffing with every key of the piano, others elsewhere weren't. Their tune remains another.

A song of shame stuck on repeat.

As the smoke from both fires whipped and tapered, you could be forgiven for seeing the spectre of hate flying out with it. Through the goalposts, over the grandstand, and across the train line. A weight removed; a wound beginning to heal.

With faces from all races singing in unison with the inimitable Uncle Kutcha Edwards, harmony was found in the forward pocket of this little pocket of country.

Even if only for a moment.